| Mp3s Biography Links Sheetmusic | Ludwig van Beethoven opus 123Missa solemnisMass 1823. Time: 71'00.Beethoven wrote the Missa Solomnis between 1818 and 1823. |

| Buy sheetmusic for this work at SheetMusicPlus |

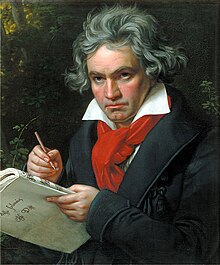

In this famous portrait of Beethoven by Joseph Karl Stieler, Beethoven can be seen working on the Missa Solemnis in D Major.

The Missa solemnis in D Major, Op. 123 was composed by Ludwig van Beethoven from 1819-1823. It was first performed on April 7, 1824 in St. Petersburg, under the auspices of Beethoven's patron Prince Nikolai Galitzin; an incomplete performance was given in Vienna on 7 May 1824, when the Kyrie, Credo, and Agnus Dei were conducted by the composer.[1] It is generally considered to be one of the composer's supreme achievements. Together with Bach's Mass in B Minor, it is the most significant mass setting of the common practice period. Unquestionably a great work, representing Beethoven at the height of his powers, it has notably failed to reach the popularity of many of the symphonies and sonatas. Written around the same time as his ninth symphony, it is Beethoven's second setting of the mass, after his Mass in C, Op. 86, a work far less admired. The mass is scored for 2 flutes; 2 oboes, 2 clarinets (in A, C, and B♭); 2 bassoons; contrabassoon; 4 horns (in D, E♭, B♭ basso, E, and G); 2 trumpets (D, B♭, and C); alto, tenor, and bass trombone; timpani; organ continuo; strings (violins I and II, violas, cellos, and basses); soprano, alto, tenor, and bass soloists; and soprano, alto, tenor, and bass chorus.

StructureLike most masses, Beethoven's Missa solemnis is in five movements:

PerformanceThe orchestration of the piece features a quartet of vocal soloists, a substantial chorus, and the full orchestra, and each at times is used in virtuosic, textural, and melodic capacities. The writing displays Beethoven's characteristic disregard for the performer, and is in several places both technically and physically exacting, with many sudden changes of dynamic, metre and tempo. This is consistent throughout, starting with the opening Kyrie where the syllables Ky-ri are delivered either forte or with sforzando, but the final e is piano. As noted above, the reprise of the Et vitam venturi fugue is particularly taxing, being both subtly different from the previous statements of the theme and counter-theme, and delivered at around twice the speed. The orchestral parts also include many demanding sections, including the violin solo in the Sanctus and some of the most demanding work in the repertoire for bassoon and contrabassoon. A typical performance of the complete work runs 80 to 85 minutes. The difficulty of the piece combined with the requirements for a full orchestra, large chorus, and highly trained soloists, both vocal and instrumental, mean that it is not often performed by amateur or semi-professional ensembles. Critical responseSome critics have been troubled by the problem that, as Theodor Adorno put it, "there is something peculiar about the Missa solemnis." In many ways, it is an atypical work, even for Beethoven. Missing is the sustained exploration of themes through development that is one of Beethoven's hallmarks. The massive fugues at the end of the Gloria and Credo align it with the work of his late period—but his simultaneous interest in the theme and variations form is more than absent. Instead, the Missa presents a continuous musical narrative, almost without repetition, particularly in the Gloria and Credo movements which last longer than any of the others. The style, Adorno has noted, is close to treatment of themes in imitation that one finds in the Flemish masters such as Josquin des Prez and Johannes Ockeghem, but it is unclear whether Beethoven was consciously imitating their techniques or whether this is simply a case of "convergent evolution" to meet the peculiar demands of the mass text. Donald Francis Tovey has connected Beethoven to the earlier tradition in a different way:

Perhaps the best way to recognize the importance of the mass in Beethoven's work is to acknowledge its singularity, and to view its remarkable variety and forceful individuality as the reflection of Beethoven's own relationship with the divine. Some have remarked[citation needed] that his treatment of the text—including the addition of a high "a," in the Miserere section of the Gloria, and the quick disposal of several lines of text in the Credo underneath the weight of the two other choral parts and orchestra—shows a willful indifference to the more dogmatic precepts of the church, while others see the forceful expression of the central movements as having a sincerity that could only be born of true belief. See alsoReferencesExternal links

| ||||

This article is licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License. It uses material from the Wikipedia article "Missa_Solemnis_(Beethoven)". Allthough most Wikipedia articles provide accurate information accuracy can not be guaranteed. |

Help us with donations or by making music available!

©2023 Classic Cat - the classical music directory

Beethoven, L. van

Symphony No. 4 in B flat major

Columbia Symphony Orchestra

Beethoven, L. van

Für Elise

Mauro Bertoli

Bach, J.S.

5 Little Preludes (BWV939-943)

Chris Breemer

Beethoven, L. van

Piano concerto No. 1 in C major

Vienna Philharmonic

Beethoven, L. van

Symphony No. 3 "Eroica"

Deutsches Symphonie Orchester Berlin

Beethoven, L. van

Piano Concerto No. 5 "Emperor"

Dimitris Sgouros